The Modix BIG-180X V4 is the latest iteration of the company’s industrial-grade self-assembly FDM/FFF 3D printer kit. It is one of the latest additions to the company’s lineup designed to provide the utmost degree of reliability and precision. Aside from an outstanding build volume, the printer offers a handful of other useful features enhanced with the Generation 4 total upgrade.

The machine introduces a bunch of redesigned key components and high-grade premium parts, namely the electronic expansion board Duex 5 enabling completely automated calibration, stronger Nema-23 motors and CNC machined brackets for much faster and more stable printing, optical end-stop switches for higher accuracy and repeatability, improved PTFE tube and wires management for smooth and convenient maintenance, built-in crash detector for additional safety, and an integrated emergency stop button ensuring immediate response. In addition, all the Generation 4 models boast updated design features, such as a pneumatic top lid, rear maintenance opening hatch, sturdy door hinges, door and lid sealing strips, and improved internal LED lighting. It also benefits from a filament sensor, which keeps track of potential clogging, and Wi-Fi connectivity for remote control. Moreover, the company has released a brand new IDEX add-on, which opens up new possibilities for printing with independent dual extruder and water-soluble filaments.

The BIG-180X is made for industrial applications and is expected to be used by experienced makers. It is perfect for prototyping, batch production, product development, sculpting, film, advertising, and a number of other industries.

Credit: @Craig Tharpe / Instagram

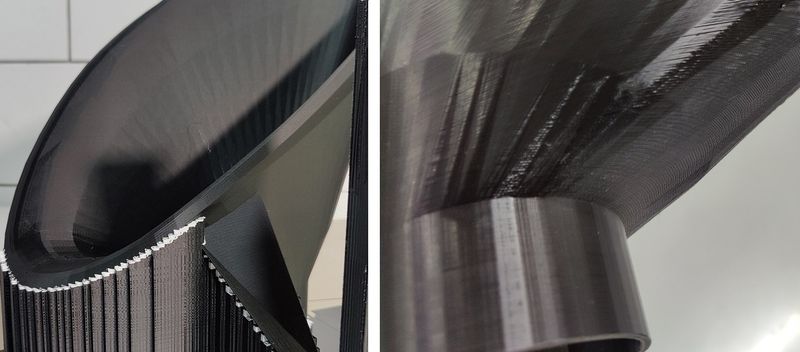

With such a large build volume and outstanding print quality, the 3D printer can be successfully applied in multiple spheres. For example, it can be used to create large models for sculpting arts.

Credit: @Efes Bronze / Instagram

The Modix BIG-180X V4 is an FFF/FDM 3D printer that can print layers at a minimum layer height of 40 μm. This way you can produce parts with smooth exterior surfaces.

Credit: @Goodyear Tires / Instagram

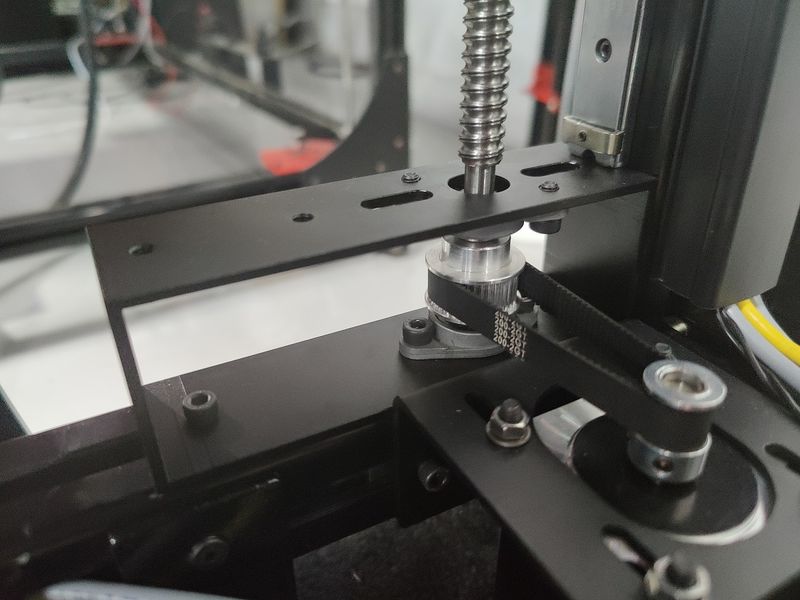

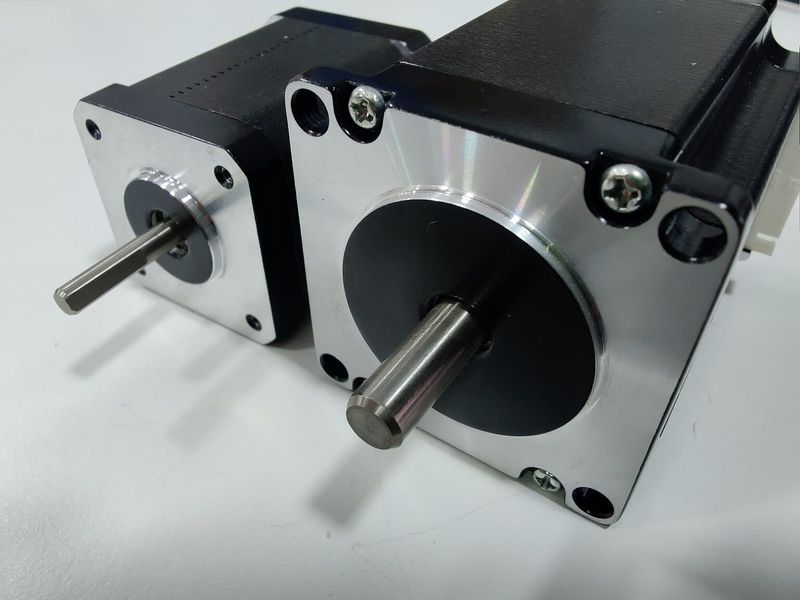

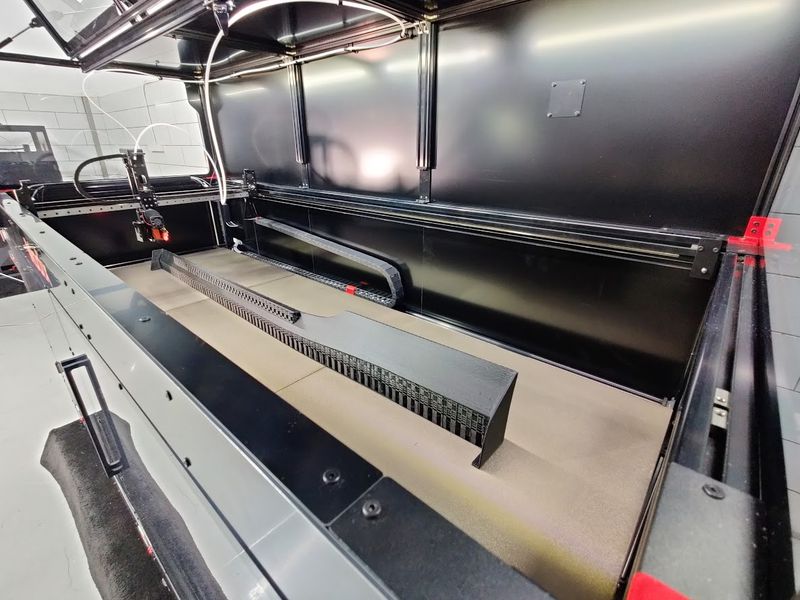

The Z-axis of the printer has been upgraded, featuring strong Nema-23 motors and reliable CNC machined brackets that hold the bed firmly and add to the overall level of print accuracy.

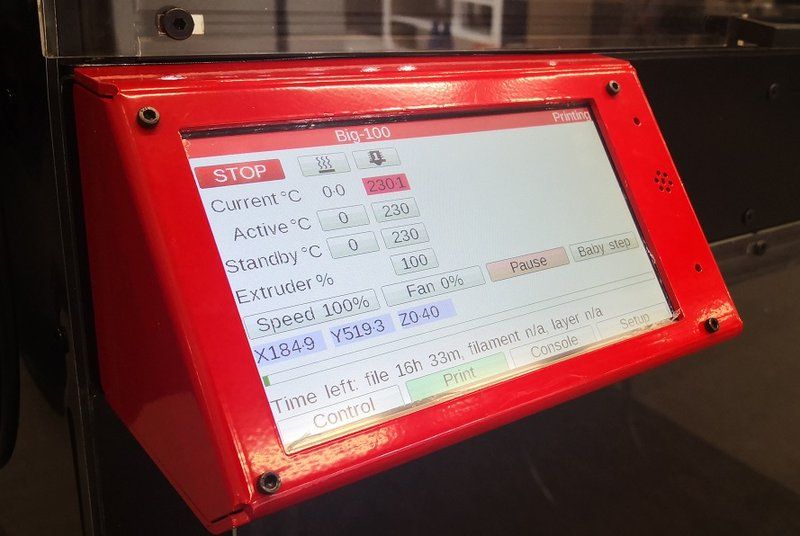

Due to the better motors on the X axis (compared to NEMA-17 motors for the V3), the BIG-180X V4 provides much faster printing than before. The machine boasts the accelerated travel speed of up to 350 mm/s and printing of up to 250 mm/s.

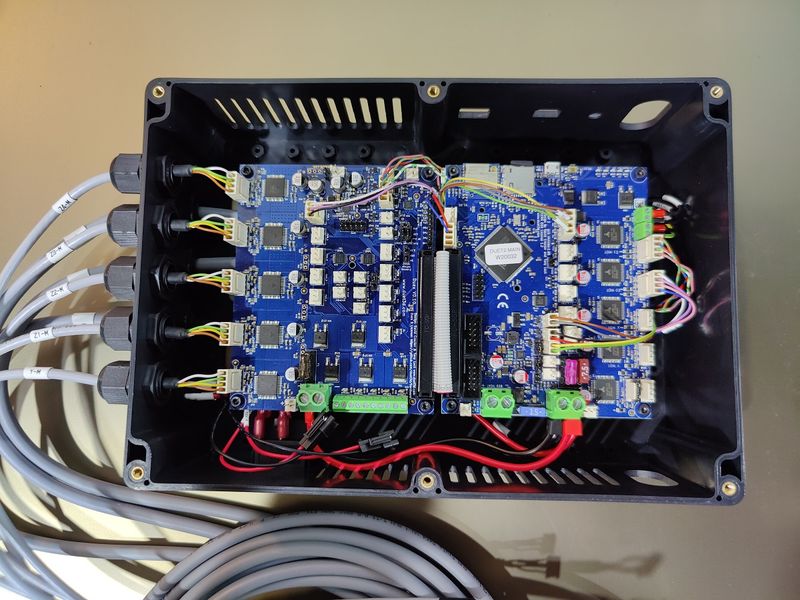

Starting with the Generation 4, the Modix devices come with the electronic expansion board Duex 5, with a dedicated stepper motor driver allocated for each Z and X axis motor. Thanks to this important improvement, the printer now offers a full set of automated calibration routines, including automated bed tilt, bed leveling, gantry alignment, and Z offset calibration making for enhanced printing precision.

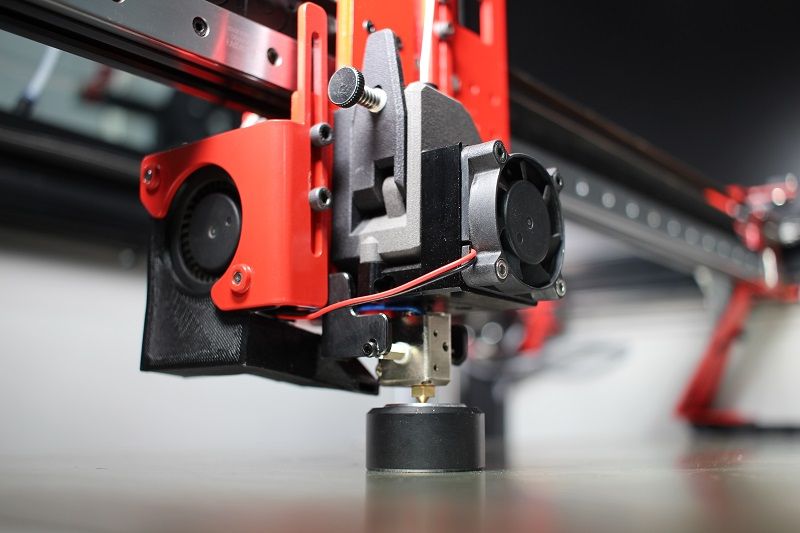

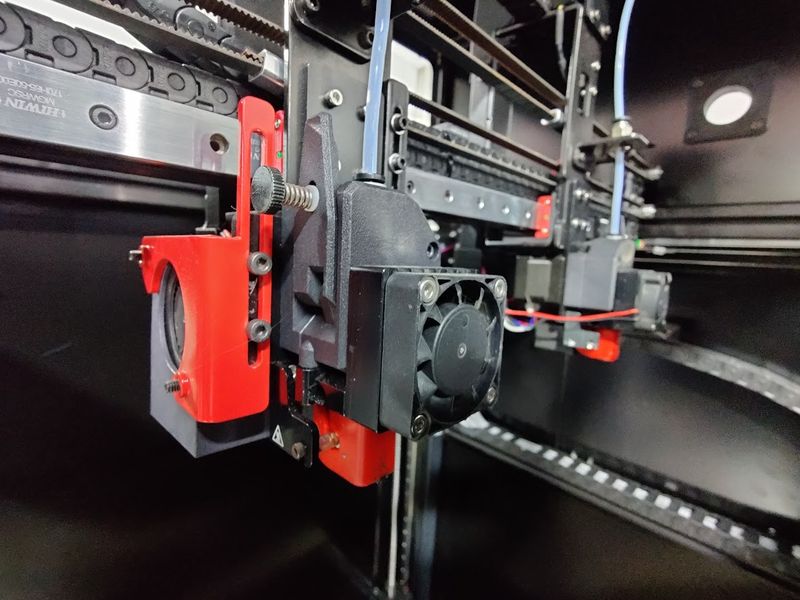

Another major improvement is the new Griffin printhead. Previously it was just an optional upgrade and now it comes as the default component on all the company’s V4 printers. It consists of a custom extruder made by Bondtech and a new hotend designed by Modix. The upgrade offers smart and compact design, high flow rate, increased reliability, easy swap, and great resistance to high printing temperatures, leading to overall improved user experience.

As for the upgraded optical end-stop switches, they provide more accuracy and higher level of repeatability over time, which is particularly important for printing recovery after power outages.

These are just some of the noteworthy upgrades featured by the new version.

The Modix BIG-180X comes stock with a 0.4 mm nozzle, giving you the best balance between speed and detail. The printer is compatible with nozzles of different sizes, allowing you to choose the best option for a particular application. It can also be equipped with the IDEX add-on for multi-material printing of complex internal geometries.

The print head runs on HIWIN motion rails, which makes printing reliable, fast and precise.

The Modix BIG-180X V4 offers a variety of filament types to choose from. It is compatible with PLA, ABS, composites such as Carbon fiber, Wood, Copper, Brass, Magnetic, PHA, PVA, Hips, Nylon, TPE & TPU (flexible), Co-Polyester, and PETG.

The optional IDEX add-on includes a secondary printing subsystem, consisting of a Griffin print head, clog detector, PTFE, and spool mount. It enables high-quality multi-color and soluble material printing.

The V4 comes with a default clog detector that can easily detect filament run-out, under-extrusion, and hotend clogs, which allows the user to quickly fix the problem and avoid negative impact on the quality of the printed items.

The Modix BIG-180X V4 features an open material system. This means you can print with any third-party 1.75 mm filament.

The Modix BIG-180X V4 offers an extra-large build volume of 71 x 24 x 24 inches (1800 x 600 x 600 mm) that lets you print just about anything. Such a build area lets you produce outstandingly large parts or simultaneously print several middle-sized models at once.

The Modix BIG-180X V4 3D printer can be controlled via PC, smartphone, or its built-in 7" LCD display with emergency stop button for smooth real-time interaction.

The BIG-180X V4 features Wi-Fi, USB, and SD card connectivity, making it a highly accessible machine.

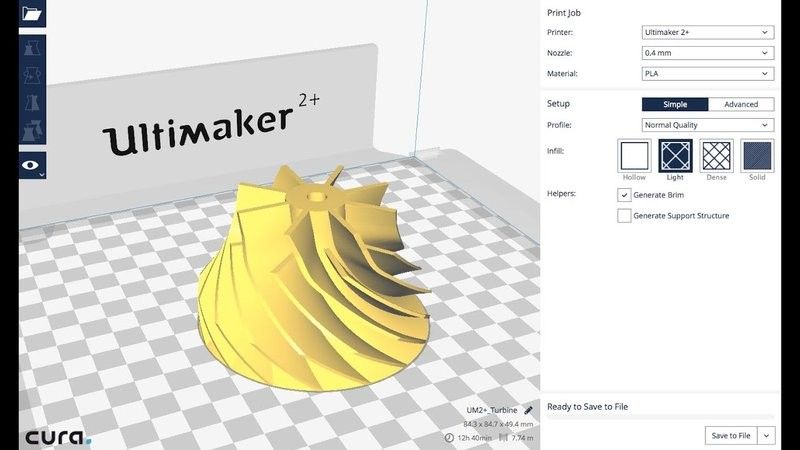

The machine can interact with 3D models of almost any format and is compatible with a number of slicing software solutions, such as Simplify3D, Slic3r, Cura, Printerface, and many others.

For some items, package content may change. In case of any questions, please get in touch.

The Modix BIG-180X V4 is available in black. Its stylish appearance, premium-grade components, and smart design make it ideal for a number of professional and industrial applications.

The printer dimensions are 85 x 42 x 56 in (2170 x 1060 x 1430 mm). The spool holder is mounted on the left side of the machine.

The price for the Modix BIG-180X V4 3D printer is $15,500.00, which is reasonable considering its functionality, impressive build area, and upgrade potential.

The Modix warranty policy is available at the link below:

https://www.modix3d.com/modix-general-terms-and-conditions-of-online-sale/

Update your browser to view this website correctly. Update my browser now